The most common representations of Arab cultures in the public domain in the UK at the time of the Zenith Symposium at the Barbican in 2004 related to Islamic culture as it was about 800 years ago. This grand past bore little relation to the equally fascinating contemporary make-up of the region, and of its post independence intellectual movements and cultural productions. This lack of attention to the living cultures from what is often generically dubbed the Arab region seemed to have a political and ideological importance that lay beyond the arts. What was needed was a more direct engagement with cultural production from the Arab region that would move the debate from the prevalent simplistic ideas at the time, which tended to centre on affirming or refuting whether there is a clash of civilisations between the Arab region and the West.

The Zenith Symposium on Modern and Contemporary Art from the Arab Region was held at the Barbican in London in the summer of 2004. It sought to engage with an audience of curators, art practitioners and funding bodies on issues relating to the representation of artists and works from the Arab region. The number and quality of attendees reflected a willingness among art practitioners to find new ways of discussing and engaging with arts from the region.

The overall lack of knowledge among international art venues and curators on modern and contemporary Arab art at the time, made it difficult to curate noteworthy, contemporary exhibitions on the subject. Without such familiarity, it was difficult to assess contemporary artists and works for quality, importance, aesthetic rigour, criticality and the like. Within this context, it seemed necessary to hold a Symposium to engage with curators, art practitioners and funding bodies directly on the issues and politics at stake. The speakers at the Symposium –Catherine David, Jayce Salloum, Stephen Wright, Saleh Barakat, Rashad Salim, and Els Van Der Plas – had already been working within the Arab region before it became an area of focus for others.

Catherine David has played an important, although controversial part in the formation of an international platform for the representation and discussion of contemporary art practices in the context of the Arab world. David’s pursuit of her long-term project Contemporary Arab Representations began in 1998 and continues until this day in different forms. David has an established reputation as an international curator, including for her work as Artistic Director for Documenta X in Kassel, Germany (1994-1997), lending weight and attention to her contemporary Art from the Arab region projects.

She has also been outspoken in relation to the uninformed criticism levied by fellow curators in relation to art from the Arab region. In answer to criticism that modern and contemporary art are a Western phenomenon best presented by Western artists, David dismisses this as essentialising and simplistic. In her words, a medium is not genetic. All you need is to acquire the ability to use and question with a medium. She parodies, or perhaps quite realistically, reflects comments she has heard from her colleagues who have patronisingly referred to modern art from the Arab region as ‘too eclectic’, ‘kitsch’, ’20-year late bad copies of someone else’. By contrast, she believes that the moment one tries to understand modern or contemporary art from the Arab region, one sees its complexities and cultural sensibilities. David’s perspective is that the creation of new paradigms is what gives interest to a work, rather than historical background or context. It could also be that the work involved in putting together an exhibition, a book or a discussion could be part of a creative and generative process of new paradigms.

As part of the Zenith Symposium, we were looking to include speakers able to provide commentary on artists and the art scenes in different countries in the Arab region and its Diaspora, rather than have artists engage with the specificities of their own work. Jayce Salloum is both artist and curator, and sees his curatorial work as an extension of his art practice. He is Canadian of Lebanese origin and has been practising since 1975, with shows curated by him as well as exhibitions showing his work,being held worldwide. His early collaborations included artists that were to become very well-known figures in the international art and film scenes, including artist Walid Raad and filmmaker Elia Suleiman. Salloum’s emphasis was on the need for curators to constantly question their and the viewers’ respective positions, “investing in each other’s subjectivities, and inter-subjectivity, speaking in collaboration/conjunction, and speaking through our articulations and mediations that reflect the nature of the complexities and layers embedded in the work”. Although this seems obvious, the reality at the time, and possibly still, is different.

There were strong reservations on labelling artists ‘Arab’ and even on discussing the region and countries within it under the general rubric of Arab, leading to a bind when talking about a region that seems impossible to name. Catherine David, Stephen Wright and Jayce Salloum all justified and qualified their references to ‘Arab art’,’ Arab artists’ and ‘Arab region/countries’, and so did Zenith when contextualising the Symposium and ensuing Arab Cities Project. These political and critical issues are still being debated today. It was interesting to note that speakers at the Tate Modern Symposia— entitled Infrastructure and Ideas: Contemporary Art in the Middle East (January 2009) –picked up the same arguments discussed in 2004, pointing perhaps to the idea that debate and conversation, rather than firm resolution, are what is at issue in the ‘Arab’ question. However, while these questions are valid and important, they can have a paralysing effect on the narrative and projects relating to art from the Arab Region. The subject descended into farce at the Tate Symposium with some speakers and audience members referring to the Arab region as the ‘thing’. Yet, as Salloum pointed out in his talk, there is violence in misnaming as well as in not naming. The ‘Region’ or ‘Thing’ are, in my view, more problematic than the imperfect name of ‘Arab’ Region. As David said at the Zenith Symposium, there is a danger with taking deconstruction too far and ‘throwing the baby out with the bathwater’.

These reservations are shared by others, including professor of art history and founding president of the Association of Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World, Iran and Turkey Nada Shabout. In an article responding to themes discussed at the Tate Symposium, she states that ’the relationship between the visual and the verbal is further complicated by a raft of factors that I argue currently hinder the advancement of knowledge in the field.’ Her personal perspective is that the term ‘Arab’ is valid because it recognises the countries’ shared historical, linguistic and cultural roots, while not diminishing the differences between them. She also makes the point that the absence of agreement about a suitable term for the visual production of the region is ’perhaps a problem today for all geographical regions in an age that is obsessed by categorisation but, at least rhetorically, simultaneously rejects essentialism’.

The picture has otherwise changed significantly since the time of the Zenith Symposium, with many artists from the Arab region being well known to most international curators, and featuring in exhibitions around the world. Does this mean that we have reached a turning point, with the challenge now being to keep this door open to more and more artists from the Arab region? Or is this ‘integration’ process retrograde, banal, and sinister when considered from the viewpoint of anyone interested in forging a ‘third space’ in the centre/periphery debate? Is it a compulsory part of the self-validation of any art practice to try and enter the fold of Western art narratives and its art spaces?

These points are picked up by Stephen Wright at the Zenith Symposium. He questioned whether it is possible to have ‘art’ and ‘artists’ in the absence of an ‘art world’ that creates narratives around works, and art histories and theories contextualising artists and their methodologies. Wright argues that, in the absence of an ‘art world’ focused on Arab art, some artists from the region have developed infiltrative themes in their works that deconstruct the very notions underpinning Western hegemony over the art world, or the socio-political world more generally. Alternatively, artists have continued to focus on their own concerns without seeking engagement with an international art world.

The Zenith Symposium – having deconstructed or challenged notions of an ‘Arab region’, ‘Arab Art’, certain Western curatorial approaches to the Region and artists from it, and the very idea of an ‘art world’ in the Arab region – took to task with speaker Rashad Salim the values and aesthetics of ‘modernism’ as evident in images that become iconic or valorised, and others that are seen as insignificant and ignored.

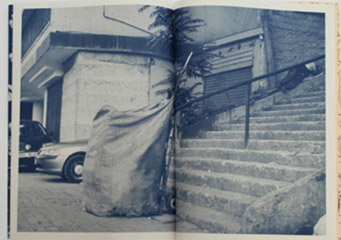

Salim comes to this issue from his background as an Iraqi artist with personal insight into modern Arab art, through family links to the famous Arab modernist and pioneer Jawad Salim, and being himself an activist campaigning against the use of depleted uranium in Iraq and elsewhere. Salim powerfully puts forward the case that what we are faced with is tantamount to the ‘death of meaning’. The media has focused on the destruction of Iraq’s past, ignoring that its modern structures have also been destroyed. The image on the cover of Desert Storm Xbox II symbolises what we have come to value and allow our children to play with. The image of the twin towers is now a totem, but how many of us have internalised an image of the carpet bombing of Tora Bora? He considers the veiling of Picasso’s Guernica at the UN during Powell’s speech on Iraq as another nail in the coffin of meaning. He asks: What are we to make of the sculpture of a hooded shackled Iraqi, exhibited in Iraq before the Abu Ghraib torture scandal became known? He juxtaposes this with ancient Mesopotamian carvings depicting slaves. However, he points out that it could equally be read in conjunction with photographs taken by the torturers in Abu Ghraib posing with their victims, as if intended for a family photo album, or with video footage taken by suicide bombers of their missions.

So, how can ‘meaning’ be resurrected? Salim argues that we should look again at ‘tradition’ and ‘nature’ for inspiration as they are the very source of art and life itself, yet have been relegated to ‘outsider status’. Salim is not calling for a return to ‘craft’, but rather for a new aesthetic, new perspectives and methodologies that are in tune with, and valorise what is really important, as well as deconstruct the causes of our increased alienation.

The Symposium was concerned with shedding light on ‘Modern Arab Art’, as well as on contemporary practices. This is not only in order to be informative about the trajectory of modernism in the Arab region, and its notable figures, it also provides interesting perspectives on whether there are any links or ruptures between the approaches of the Arab modernists and contemporary artists from the Arab region. Saleh Barakat, an established curator and gallery owner based in Beirut, with great knowledge of modern Arab art works and artists, focused on illustrating how, in the case of the leading Arab modernists such as Shaker Hassan Said, any methodological similarities between Western and Arab modern art did not necessarily entail the same conceptual departure points. Indeed, the Arab modernists wanted their art practices to be distinguishable by their own post-colonial concerns and regional belongings.

By contrast to the problematisation of an ’Arab’ identity by contemporary artists, many modernists sought to reinforce this identity through their works. This was not in allegiance to any political forces, but an expression of an inclusive, secular or even multi-religious perspective on the region. This perspective chose language, spiritualism, and other non-divisive local traditions, mythologies, and histories as a common denominator that anchored their art to their respective countries, and possibly to the region. They were also forward looking and modern, choosing the abstraction of modernism as their medium or language. This abstraction is of course itself rooted in the Arab region, with Islamic abstraction having been one of the influences (albeit not always acknowledged) on western abstraction. However, it will be a mistake to confine the importance of their works and its readings to a post-colonial Arab context, as their works allow for multiple interpretations and are timeless in their appeal and relevance.

Curators, artists and writers can be seen as part of a dynamic trio that can work in conjunction with one another, or feed off one another, to create new paradigms. Funding bodies are the fourth element in the dynamic that shapes artistic representation. Ultimately, it could be said that it is down to them what artists, exhibitions and projects receive sufficient financial support or succeed. As such, the Symposium wanted to introduce the perspective of an art funding organisation, and this talk was given by Els Van Der Plas of the Prince Claus Fund. She spoke of the Fund’s ‘Creating Spaces of Freedom’ theme which was introduced in 1999. She explained the aims of the fund as supporting intellectuals and artists suffering from lack of funding infrastructure in their countries, and that come from places short on political freedoms. Van Der Plas explained that their aim is to support projects or practices that ‘seek out the places of social elasticity’. It was interesting to have this concept illustrated by works that fall within its intended meaning such as the Arab Image Foundation’s Van Leo Project, Walid Raad’s Atlas Group, Jayce Salloum’s In/Tangible Cartographies, Moataz Nasser’s Tabla, and Rula Halawani’s Photographs of the Qalandia Israeli Checkpoint.

Is the process of seeking to carve out a space on the international art platform for art from every region of the world, including the Arab region, an inevitable impulse in an ever ‘smaller’ and inter -related world? In doing so, one needs to take stock of issues and pitfalls, such as the ones highlighted by the Zenith Symposium, to help forge a new direction and move the discussion onto a different level. This is what Zenith sought to do in its follow up to the Symposium, namely in the Arab Cities Project leading to the UK exhibition New Ends, Old Beginnings.

Chourouk Hriech is an artist thriving on multiple belongings and constant travel. Born in France of Moroccan decent, she divides her time between Morocco, France and other destinations. Hriech’s drawings reflect this confluence of inspirations and experiences, also incorporating the mythological and imaginary, resulting in the creation of social-historic frescos that depict vibrant urban improvisations.

Chourouk Hriech is an artist thriving on multiple belongings and constant travel. Born in France of Moroccan decent, she divides her time between Morocco, France and other destinations. Hriech’s drawings reflect this confluence of inspirations and experiences, also incorporating the mythological and imaginary, resulting in the creation of social-historic frescos that depict vibrant urban improvisations.

It is often a confounding moment when a performance of free improvised or experimental music starts or ends. A few seconds of silent hesitation denote the audience’s anticipation, is it time for applause or for more listening? In light of these frequent occurrences, musicians tend to take on a more relaxed body posture and less concentrated facial expressions to mark the end of a performance, often with a smile as if to say: “Yes, you can now applaud, boo, do what you want, it’s over”..

It is often a confounding moment when a performance of free improvised or experimental music starts or ends. A few seconds of silent hesitation denote the audience’s anticipation, is it time for applause or for more listening? In light of these frequent occurrences, musicians tend to take on a more relaxed body posture and less concentrated facial expressions to mark the end of a performance, often with a smile as if to say: “Yes, you can now applaud, boo, do what you want, it’s over”..

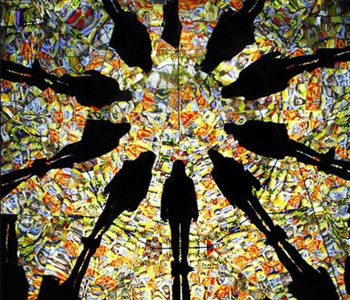

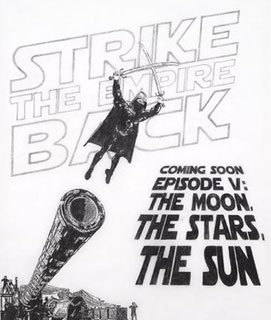

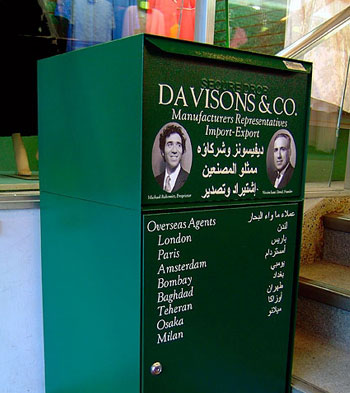

What do Jules Verne, Andree the Giant, Darth Vader and Sgt. Slaughter all have in common? Like a surreal game of Six Degrees of Separation, these characters are seamlessly linked in artist Michael Rakowitz’s latest exhibition at London’s Tate Modern entitled ‘The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own’ (2010). Employing the humour, wit and research strategies akin to investigative journalism, he deftly exposes the finely spun webs connecting seemingly disparate elements across times, geographies and histories. Rakowitz is interested in making the invisible, visible, and in revealing the latent circuits of power and politics that shape daily realities.

What do Jules Verne, Andree the Giant, Darth Vader and Sgt. Slaughter all have in common? Like a surreal game of Six Degrees of Separation, these characters are seamlessly linked in artist Michael Rakowitz’s latest exhibition at London’s Tate Modern entitled ‘The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own’ (2010). Employing the humour, wit and research strategies akin to investigative journalism, he deftly exposes the finely spun webs connecting seemingly disparate elements across times, geographies and histories. Rakowitz is interested in making the invisible, visible, and in revealing the latent circuits of power and politics that shape daily realities. U.S. under such restrictive measures, the date syrup’s circuitous route — having been produced in Iraq, trucked over to Syria, packaged in and shipped from Lebanon – seemed to echo that of refugee and migrant bodies fleeing the violence in Iraq.

U.S. under such restrictive measures, the date syrup’s circuitous route — having been produced in Iraq, trucked over to Syria, packaged in and shipped from Lebanon – seemed to echo that of refugee and migrant bodies fleeing the violence in Iraq.

How long have you been living in France?

How long have you been living in France?