Lara Baladi: Domestic Excess and Recycling

Lisa Skuret

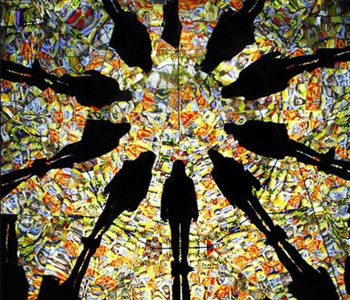

Roba Vecchia, The Wheel of Fortune (2006)

Gregory Bateson (Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 2000)

Lara Baladi’s work is about time, (re)fabrications and methods of dispersion. This preoccupation may stem, in part, from her own nomadic history – being born in Lebanon, educated in London, lived in Paris and currently residing in Cairo. Having been shown worldwide, Baladi’s work also displays many international stamps in its passport. Soon to take part in Sydney Biennial (2010), she has also shown her work in exhibitions spanning from Liverpool to Mexico City and Tokyo. Similarly, the content of her work, which makes use of cliché and kitsch, as well as utilizes various modes of media dissemination, transverses formalized territories – especially that between high and low cultures. For example, an extracted version of her video installation, Shish Kebab (2004) – which was shown in Africa Remix the touring survey exhibition on contemporary African art, and which made it’s way to London’s Hayward Gallery in 2005 – was also included as part of an online exhibition on ‘identity’ for the British fashion magazine, i-D.

In the text accompanying the two-minute version of the video for i-D magazine, Baladi says that Shish Kebab was “an expression of a nostalgic desire for an imagined world”, revealing perhaps one of the fundamental concerns which inhabit her work. At first glance, this fragment from a more protracted quotation seems to contain a contradictory blend of past and future, of both nostalgia and sci-fi. It refers in part to the complicated relationship between fiction and the fabric of the known, as well as to the place and function of memory within the future. Simultaneously, this temporal imagined world could refer to the potential of the future, as well as to something which already exists, but in absentia. As in the case of nomadic emigration, it refers to the emigree’s absence from his or her place of origin, their exile, and points to the potential of conjuring a fictive, imagined world in relation to that place. Baladi’s work is concerned with these contradictions inherent within the constructions of time, and within her artistic explorations, she experiments with recycling as one potential method of projecting time beyond its frames.

Baladi works primarily within the photographic medium, where historically, the image can be seen as a stand-in, pointing to or documenting the validity of the past. Her work, which encompasses collage, video and installation, questions the authenticity (and authority) of memory as a type of museum culture, opening up the chronological flatness of these images, rendering their references unstable and their meaning unreliable. One could say that she uses images as cognitive collages, playing with the concept of a single photographic as well as temporal, and cultural frame.

Images within contemporary digital culture have an indefinite reproductive capacity and are therefore more expendable. How do we negotiate our media-constructed landscapes and what do we do with the excess of images? Easier access to the technologies of (re)production has historically led to the development of temporary, contemporary pop and ‘trash’ cultures. Baladi, not limited to the streets of Cairo, but also trawling the urban landscapes of countries including Japan, India, and the United States, works as collector-explorer of this (multi)cultural (or is it now global?) excess. In her artistic process, she often recycles found domestic waste and the ruins of commodity production which she then (re)distributes in a variety of ways. For example, she playfully repurposes collective memories (in the iconic images of domestic brands) of Egyptian childhood onto t-shirts, and through artworks such as Diary of the Future (2007-2008) and Roba Vecchia (2006-2007) she recycles the past as future.

Roba Vecchia (translated from Italian as ‘old stuff’, or more colloquially as the ‘same old story’) is not a fixed piece, but perhaps more akin to a work in progress, a progression that has thus far taken on two kaleidoscopic forms. The first form, an interactive installation entitled Roba Vecchia, The Wheel of Fortune (2006), has since been recycled into Roba Vecchia (2007), a piece in which images generated from the initial installation were mounted onto a sheet of mirror-polished, stainless steel.

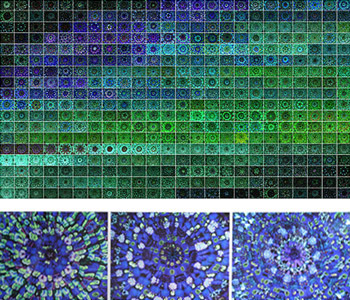

Roba Vecchia (2007) and detail.

Looking at the work’s second incarnation with the perspective of distance, my first inclination was to divine a system. The work looks like an html color chart, but closer inspection reveals a series of quasi-Islamic mosaic patterns creating a decorative, tiled surface or zellige. Looking closer still and focusing on a single tile or framed ‘image’, one notices that it is itself comprised of many other images radiating from a central axis. Up close, there is nothing orderly or precise about these single compositions – similar to arabesque designs’ almost imperceptible non-symmetry, they arguably contain a human imperfection and appear incomplete. While each image is contained within the overall pattern created by the piece, like images momentarily created by a kaleidoscope, they give the illusion of activity beyond the artificial confines of the grid – a kind of psychedelic excess. The radiating patterns act like little vortices whose temporary configuration gathers everything in its path – including the viewer (the image religiously excluded from the classical arabesque) who, within the reflective surface of the work, seems to temporarily occupy an arbitrary point within an infinitely extending expanse.

In its alternate form, Roba Vecchia is an installation with the addendum The Wheel of Fortune in its title. In this (2006) piece, a mirror-lined tunnel provides vertiginous access to a temporal landscape constructed from a continuous reconfiguration of ready-made image fragments projected onto its surface. For this piece, Baladi used a computer program to momentarily code or assemble these new geographies or narratives from the old stuff, the old story, the leftovers. In this instance, the leftovers are fragments from her artistic process, which were in turn constructed from images of personal and cultural (over)production and ‘trash’ or pop cultures. In the interactive installation, this inherited surplus extends to include the participant whose image is captured, incorporated into the system and projected within the installation. Drawing from a pool of both presently captured and previously inputted images, in the ‘Wheel of Fortune’ the present is created by random (re)assembly and mutation. In this way, the work seems to be a continual and dynamic process of scrambling and assembling code, and creating new code in the form of questions such as: In what way is the ‘leftover’ like memory? What role do personal and collective memories play in constructing a landscape of the future? Has my memory mutated into fiction? And where am ‘I’ (perhaps presently existing as a leftover of memory) within it?

The images in both incarnations of Roba Vecchia are volatile. Momentarily capturing the image, reflective surfaces create an illusion of depth providing a multidimensional platform for projection and reproduction and, in simultaneous contradiction, for refraction and dispersal. The reflected image, like the photograph, acts to create a representation or an illusion of reality while inventing a fictional point of view. This also points to the role that recognition (or lack thereof) has to play in constructions of the future. We encounter different configurations of the same stuff, and this process of (re)configuration or (re)cycling becomes a mode of transport to alternative imagined worlds. Similar to the practical work of memory as a navigational tool, Baladi’s work draws on, and is in some sense determined by, images from the past. Despite this, the memory-work migrating into its present configuration does not seem limited by determinism. The old junk has been recycled in a way that is not immediately recognisable as domestically useful. The mirror has, in a way, been transformed into a window onto a temporal and fictional landscape.

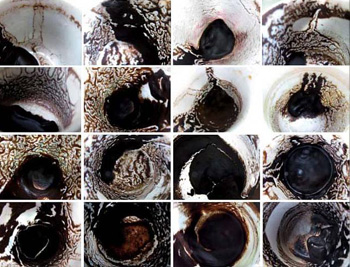

In another progressional work, Diary of the Future (2007-2008), a recent photographic commission for the group show entitled New Ends, Old Beginnings in Liverpool’s Bluecoat Gallery, Baladi returns to a grid pattern or timeline – assembling and attempting to link (un)related temporal moments into a chronological system or code of meaning. The work of assembly began during a period of her father’s illness, as she documented the daily visits made by friends and relatives in an attempt to predict the future from the residue left behind in their coffee cups.

The title of the piece, Diary of the Future, like the earlier quoted fragment from i-D, alludes to the complex interaction of different temporalities, tenses and codes of language. The interaction of temporal discontinuities is perhaps an exercise in predictive futurities, a form of fortune-telling, and would imply that the future for Baladi already exists within the system and within the past. This conception of time is similar to the one depicted in many science-fiction films, in which the future is almost always recognizable, a variation on what is actually already there, and exists as the continuation of a cycle projected or predicted into the future. It is one consequential outcome out of many almost inevitable outcomes. Like fortune-reading, the function of psychoanalysis is the recognition of patterns which may exist as unconscious to the analysand. Fortune-reading, psychoanalysis, and one could argue art, explore the waste resonating from this both personal and collective, intercultural junkyard in order to break with habitual symbolic encoding. The temporal breaks or pauses, in Diary of the Future as in Roba Vecchia, interrupt our reading of the material and allow for a moment in which patterns may be reconfigured and a new story assembled – these variations on the old story point towards potentially different futures.

Diary of the Future (2007-2008)

(A) reading is often based on recognition and repetition of images, and one can only clearly come to decipher patterns from a perspective of distance. It is significant to mention here that Baladi’s work is often presented in large-scale formats, and has been described as ‘life-sized’. Being life-sized, her work often creates a landscape, which implies a potential human presence – an agency. Similarly, when immersed in any constructed landscape, urban or otherwise, unable to see very far into the distance, one can lose a sense of perspective. Thus Diary of the Future begs the question: Are we predicting the future or looking at the past? Are we reading a codified inheritance rather than an unknown future? Can we create a future by linking individual ‘futures’ into a new configuration? In this piece, as in Roba Vecchia, Baladi plays with these temporal contradictions, offering them up in the interplay as questions, while resisting closed explanation.

Throughout her travels, Baladi seems to be asking the question: Where is the future? The ‘old stuff’, or more likely the ‘old story’, seems not only to point backwards towards clues, but towards a way out of a cartographic holding pattern. The title of the exhibition for which Diary of the Future was commissioned, New Ends, Old Beginnings, asks a similar question: Where does the past end and the future begin? Perhaps the answers already exist within the terrain of the question. While the exhibition title (and the exhibition itself) functions to shuffle ready-made assumptions, it also suggests an inherent circularity which depends on recognition in order to temporarily fix its identity and give it meaning.

Lisa Skuret is a writer and artist. She studied Contemporary Art Theory at Goldsmiths College London (AHRC Research Award 2007-08), Interactive Media at University of the Arts London, and Psychology at Smith College (USA) and University College London. Currently, she is working with Vision Forum (Linköpings University, Sweden) on a two-year funded research project in London. Lisa contributes writing to international visual culture magazines and also writes fiction. Recent exhibitions include ‘Fig. 4:’ at David Roberts Foundation (DRAF) London, and recent publications include Time Capsules and Conditions of Now (2012).

www.lisaskuret.com

http://mep.metrohm.com.au/2015/08/19/nirs-for-blending-and-refinery-processes/

Lara Baladi was featured in the New Ends, Old Beginnings exhibition.