Jim Quilty

A Play by Rabih Mroué and Lina Saneh

April 28-30 2010 at Monnot Theatre, Beirut, Lebanon

Over the last decade or so, a small cluster of Lebanese artists have attracted a certain degree of international critical attention. In an effort to distinguish them, writers have noted that all these artists came of age during Lebanon’s long civil war and that politics plays a more or less latent role in their practice.

Rabih Mroué and Lina Saneh emerged from this generation of Lebanese artists. Like their colleagues, both have generated a wide array of solo work in a range of media – video and on-line installation, photography and theatre – yet Saneh and Mroué are best known for their collaborations in performance.

At their best, these thoughtful, critically informed and formally innovative works speak to local and international audiences with a seriousness that does not eschew humour, and a political engagement that usually avoids the pitfalls of partisan pamphleteering.

Photo-Romance, the duo’s latest collaboration, continues this dialogue between politics and aesthetics.The play is premised on the efforts of a pair of playwrights named Lina Saneh and Rabih Mroué to make a Lebanese adaptation of an (unnamed) Italian film (the way the play oddly averts its gaze from its source text will be taken up below). The action finds Saneh’s fictive self presenting the work to an unnamed male character (Mroué). His job is to evaluate the adaptation’s “legality and originality”, and therefore his role corresponds to that of censor and critic.

If

Photo-Romance ranks among the team’s more successful works, it isn’t because it necessarily breaks new formal ground, or proposes new narrative and technical innovations to elaborate them. Its success as theatre springs, rather, from its generous embrace of its audience(s).

Attitudes about audience differ amongst Saneh-Mroué and their Lebanese colleagues. New York-based Walid Raad, a contemporary of comparable international stature, offers a point of departure. During an interview conducted at the opening of ‘A History of Modern and Contemporary Arab Art _ Part I _ Chapter 1: Beirut 1992-2005’, the artist’s first Middle East solo exhibition in 2008, a journalist asked Raad about audience and reception.

“There are two ways of viewing this question of audience and reception,” Raad replied. “On one hand we could see art as communication and learn something from the tools of public relations firms – with their focus groups and the like [and all that suggests about embracing the commodification of art] … If, on the other hand, you believe that the function of art is not reducible to communication … [then you can perceive the relationship between audience and artist differently].

This attitude is to be contrasted with that of Mroué-Saneh. Though, like Raad, their work is more often shown abroad than in Lebanon, both Saneh and Mroué have gone on record as saying that their plays are written primarily for the Lebanese audience.

That said, their embrace of the audience is an ironic one.

Photo-Romance is, among other things, an amused rumination upon the challenges of delivering a work to its intended audience, with the conceptual distinction between collaboration and censorship made playfully vague. Saneh and Mroué’s Lebanese audience is intimately aware of these challenges because so much of their theatrical work has run into problems with the Lebanese censor.

Who’s Afraid of Representation? provides one case in point. This work premiered in Beirut in November 2006 during Ashkal Alwan’s Home Works forum on cultural practices. The play was doubly offensive to the Lebanese censor. On one hand it drew upon art history depictions of performance pieces that work in self-abuse, nudity and scatology. On the other, it recounts a massacre carried out by a fictive civil servant, one that echoes an incident from recent Lebanese history.

Consequently,

Who’s Afraid of Representation? had three different incarnations during its three-night Beirut run, as the players’ worked to reconcile their demands for free expression with those of the Sureté-Géneral’s censor.

The reaction to 2007’s

How Nancy Wished that Everything was an April Fool’s Joke was more dramatic. The play, co-written by Mroué and Fadi Toufic, depicts Lebanon’s history of civil conflict from 1975 to 2007 from the perspective of four fighters, each of whom belonged to a succession of different Lebanese parties. The piece was first mounted in the Tokyo International Arts Festival in March 2007, and was scheduled to be staged in Beirut in August of the same year, followed by shows in Paris, Rome, Cairo and Rabat. Efforts to get the censor’s permission to stage the play in July 2007 resulted in outright ban, later overturned.

Photo-Romance has had a similar performance history. Created in 2009, it has lived most of its life overseas, remaining invisible to Beirut audiences until the spring of 2010, when it was staged three times to capacity audiences.

If these audiences saw more or less the same play, it was because the artists didn’t submit the text to the censor beforehand. Like all of Mroué and Saneh’s theatrical collaborations,

Photo-Romance was well attended but had a brief run of less than a week, so it didn’t attract mass public attention.

It would be reductive to characterise this play as a theatrical condemnation of state restrictions to artistic expression. Its playful dissection of the various stages of a creative process engages with the different facets of collaborative art, from creation to reception. Indeed, the play’s closing gesture – in which Mroué’s character literally abandons his censorious role for a performative one – suggests that the urge to make art is intrinsic and, ultimately, more important than questions surrounding its reception.

The play unfurls before the audience to reveal a work dismantled – like a clock disassembled in a workshop – whose ‘plot’ revolves around the characters’ picking up these components and interrogating them.

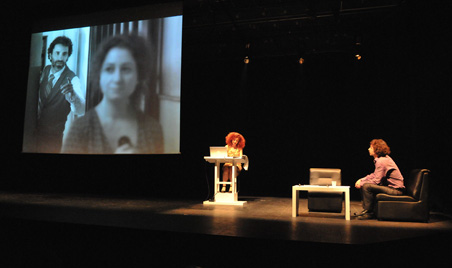

In this regard, the play’s set design (by long-time collaborator Samar Maakaron) is less a naturalistic simulacrum of an office than a dramaturgical microscope – a precision tool for scrutinising the work as it unfolds.

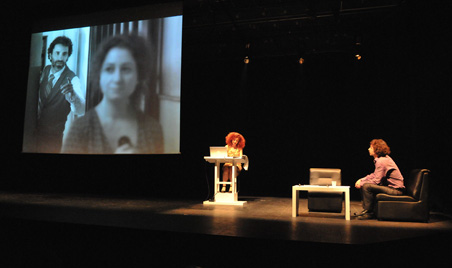

A pair of leather chairs and a coffee table sit down stage left, where Saneh and Mroué’s characters have their formal exchanges. Nearby is a lectern, where Saneh repairs from time to time to read from the film script. Next to the lectern is a cinema-sized film screen, upon which excerpts of the adaptation are projected.

On stage, Saneh plays her fictive self. The audience also finds Saneh on screen, where she portrays the female lead in their film, also named Lina. Similarly, Mroué’s on-stage character is complemented by his on-screen portrayal of the film’s male lead, also named Rabih. They play themselves as not themselves.

The third on-stage presence is Lebanese indy rock and free improvisation guitarist Charbel Haber, who – nestled with his guitar among an array of peddles and other sound equipment down stage right – awaits cues to perform the film’s soundtrack

which he was commissioned to compose.

This film-within-a-play is comprised of two “plots”. The “film” – a series of black-and-white photos presented as stop-motion animation – depicts an encounter between two Beirut neighbours. Both characters find themselves alone at home while their neighbours have joined the rest of the city in two opposing demonstrations in downtown Beirut. Saneh’s character is a divorced mother who lives with her mother and a large extended family while Mroué’s is a leftist journalist whose political views have recently got him sacked.

The framing narrative – a play about adapting a film – consists of Saneh’s depiction of the film project and Mroué’s evaluation of its various components. At times he will interrupt to ask questions. At others he will interject that some lines (references to the Lebanese army, say, or the Islamic resistance) must be struck from the script.

Local and international audiences who have followed their past collaborations will immediately recognise Mroué and Saneh’s fingerprints in

Photo-Romance. Yet, for all the evident continuities linking the play to their previous work, there are also discrete departures.

The question of representation, artistic or otherwise, has been a leitmotif in Mroué and Saneh’s writing, and the mediating screen and use of projected images have long been a part of their stagecraft. ‘Photo-Romance’ marks the first time the team works with a director of photography, Sarmad Louis.

As its title and much of its discursive content suggests,

Photo-Romance ponders the love affair artists and audiences have shared with beautiful images. In this regard, the beauty of Louis’ photography provides an appropriate object for audiences’ photo-romantic obsessions.

The title also signals Saneh-Mroué’s first flirtation with popular sentimentality – the sort of auteur engagement with popular melodrama that can be detected in some art house cinema. In

Photo-Romance, the soap-opera aesthetic is embedded in the climactic moment of the film adaptation, when Mroué and Saneh’s on-screen personae embrace.

As an enactment of the many fingers in the pie of artistic creation, presentation and consumption,

Photo-Romance raises a plethora of themes upon which audiences – whether art-headed foreigners or politically-informed locals – can reflect, between chuckles.

The play is replete with dualities. Discussions of “adaptation” immediately evoke dual notions of the “original” and the “copy.” This aesthetic duality has an ironic political Other in the two armed camps into which the Lebanese polity has a history of dividing itself – most recently, the “March 8” and “March 14” political groupings, which the play references.

Once you start evoking dualities, others crowd into the frame. By enacting a process of adaptation, the play affords ample opportunity to masticate amusingly upon the at times false dichotomies littering the landscape of artistic practice – authorship and audience, actor and character, fact and fiction, cerebral and sentimental, individual and group, man and woman.

One of the themes the artists have picked up to run with is the aesthetics and politics of absence. This has been a self-conscious element of the duo’s previous works, such as the disembodied antagonism of the interviewer in

Biokhrafia (2002), or the multiple absences of the employee in L

ooking for a Missing Employee (2003).

In

Photo-Romance, variations on a theme of absence are tossed about like playing cards at an all-night poker game. It begins with the opening gesture of the play, which appears to have a false start as, a couple of minutes into the opening video presentation, Saneh strides on stage screaming to stop, upbraiding Mroué and Haber for starting without her. The play – that is, the depiction of the film and the evaluation of its ethical creative worth – commences, literally, without its author.

This absence seems to signpost one of the themes the artists have repeatedly addressed in their work – namely the lamentable primacy of the group, family, sectarian or tribal – over the individual. “[Once one] gets lost in all these crowds,” Mroué’s on-screen character remarks of the film’s off-screen political rallies, “One becomes invisible, a mere number.”

Elsewhere, absented information is used for comic effect. When, during Saneh’s presentation, the photo of a mysterious woman appears on-screen for a couple of seconds, the censor asks who she is. “Images are like ghosts,” Saneh tells him. “They suddenly appear and just as suddenly disappear. We must respect their ways.”

Later in the presentation, the censor asks what Saneh’s on-screen character keeps clutched to her chest while she’s visiting Mroué’s apartment. It’s her character’s cat, she explains. A few scenes earlier, the pet had escaped from its cage and flown across the street to the neighbour’s balcony. This departure from the Italian original (in which the escaped pet is a mynah bird) is made all the more comic by the fact that its absurdity warrants no mention by any of the characters.

Audiences would also find the play littered with references to absences that – like Hizbullah’s “hidden” weapons cache – have more explicit political referents. Most prominent is the censor’s repeatedly reiterated order to excise certain lines from the script. A “racist” reference to Sri Lankan domestic workers must be cut, he says, as does any mention of the Lebanese army or the Islamic resistance, including a well-known anecdote involving party Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah and one of his admirers. It is tempting to see this abundance of absence as an ironic reflection upon contemporary art’s fetish with erasure as a spiritually emptied approximation of the sublime.

Perhaps the most-significant absence in

Photo-Romance, however, is the name of the source text that the artists want to adapt. For the cognoscenti in Saneh and Mroué’s audience, the unnamed original is obviously Ettore Scola’s 1977 film

A Special Day.

The political setting of this minor classic is Rome on that day in 1938 when Adolf Hitler made a state visit to see his confrere Benito Mussolini. In this film, the entire city seems to be off attending a rally to honour these two variations on a theme of national socialism, leaving the film’s protagonists – Antonietta (Sophia Loren), an overworked, barely literate housewife and mother of six, and Gabriele (Marcello Mastroianni), a radio announcer sacked from his job because he’s gay – to have their comic, humane encounter.

Were it made explicit, the setting of the source text would reverberate loudly in Lebanon, where it has long been a trope of anti-Hizbullah criticism that the party’s theatrical instrumentalisation of anti-Zionist militancy is a discomfiting echo of national-socialism. To the playwrights’ credit, ‘Photo-Romance’ suggests that both the political camps into which contemporary Lebanon has divided itself, live up to the fascist epithet equally well. It can be assumed that any implied parallel between Fascist Italy and contemporary Lebanon would not survive the censor’s flensing knife.

Yet the politics of adaptation that linger, latent, in this play is not simply a creature of Lebanese parochialism. One of the tales that has arisen about

Photo-Romance has it that Saneh and Mroué actually did approach Scola’s estate requesting permission to make a Lebanese adaptation of the film. The project was never realised since they were not granted the permission to go ahead. This meta-textual anecdote goes far in explaining the least naturalistic element in

Photo-Romance, which is Mroué’s on-stage character.

Designated “the Judge” in the English-language version of the script, Mroué’s character is the gatekeeper of both the legal and aesthetic worthiness of the adaptation. He embodies both censor and critic. But insofar as both censor and critic purport to labour on behalf of “the public”, he stands in for the audience as a whole. Insofar as the gatekeepers of the source text were themselves asked to collaborate – and ultimately blocked, the adaptation – he speaks for the original text as well.

If this character suffers from contradictory demands, the point underlines the near impossible task facing the contemporary playwright, personifying the contradictions facing any artist concerned with creating work with an audience in mind.

At times, Mroué’s character seems well-read and discerning. When Saneh tells him their work is inspired by a film set in Rome in 1938, he recognises it immediately without hearing the title. Later he reveals that he’s familiar with the works of the famed Argentine fiction writer, Jorge Luis Borges.

At the same time, his response to Saneh’s explanation of the work is often confused and child-like. Early on, Saneh explains how her troupe struggled to economise on the number of actors, though the opening scene includes an extended family preparing to go to a mass demonstration in downtown Beirut.

In the opening sequence of the film extraneous characters are in bed — hidden beneath duvets, their voices heard on a soundtrack. Later, the camera finds the duvets thrown back and the beds empty. “Wait a minute,” interjects Mroué’s character. “What is this? I can’t make heads or tails of it. Who’s speaking and who’s answering? … It’s a mess.”

Saneh then plays a second version of the scene, in which all the characters have been rendered in a child’s drawing. This time, the image-fixated audience’s job is made easier because each cartoon figure is coloured in bright crayon each time it speaks.

“What do you think?” Saneh smiles. “Isn’t it better like this?”

“Excellent,” Mroué’s character nods. “Excellent.”

Here, he represents the popular audience’s bafflement with Saneh and Mroué’s more-cerebral work – the function of the Lebanese censor being to lower the creative and critical bar to the lowest possible notch. The role of Mroué’s character isn’t restricted to cutting content, however. Like other censors, he sometimes suggests how an offensive passage of a play can be re-written to make it acceptable – making the censor the artist’s de facto collaborator.

In the final moments of the work, Mroué’s character is anxious to abandon his role as gatekeeper and to fully embrace the role of creative collaborator. He crosses the stage, picks up a toy harmonium – the actor-playwright having also worked as a musician, collaborating most notably with Lebanese vocalist Rima Khsheish – and joins Haber in playing the final bars of the film’s soundtrack.

Near the end of the play, Saneh’s character suggests that the “point” of the play’s concern with both absence and dualities is the conundrum she and Mroué have often confronted during the creative process. Contrary to what the whole movement of the play would suggest — that art is limited by the fact that, from conception to execution to reception, it is collaborative — this problem lay in the question of origin.

“The question remains,” she says, “What does original mean? Is there an origin to start with? According to us, there is no such thing […] And all our work today is about how there is no longer anything to create. So rather than […] believing that one is creating something new, let’s reveal the truth of the creative process as nothing but a construction on and a diversion from a previous work, which was itself a construction on and a diversion from a previous work ….”

All art is derivative, Saneh suggests. But more importantly, the putative origin of art, the “original”, is a phantom. It is an appropriately Janus-faced conclusion. As Mroué crosses the stage and brings the bright-green plastic harmonium to his mouth, it is difficult to see the gesture as anything but optimistic.

– fin

Jim Quilty is a Beirut-based Canadian journalist, and the editor of the arts and culture desk of the Lebanese English language newspaper The Daily Star. He has written about the arts, cultural production and politics of the Middle East and North Africa for over a decade. He is a big fan of physical comedy, with a special interest in the thump and crack of politics and cultural production as they knock against each other. His published articles appear in such magazines as Bidoun, FlashArt, ArtReview, Majella, Variety and MERIP.

Chourouk Hriech is an artist thriving on multiple belongings and constant travel. Born in France of Moroccan decent, she divides her time between Morocco, France and other destinations. Hriech’s drawings reflect this confluence of inspirations and experiences, also incorporating the mythological and imaginary, resulting in the creation of social-historic frescos that depict vibrant urban improvisations.

Chourouk Hriech is an artist thriving on multiple belongings and constant travel. Born in France of Moroccan decent, she divides her time between Morocco, France and other destinations. Hriech’s drawings reflect this confluence of inspirations and experiences, also incorporating the mythological and imaginary, resulting in the creation of social-historic frescos that depict vibrant urban improvisations.

It is often a confounding moment when a performance of free improvised or experimental music starts or ends. A few seconds of silent hesitation denote the audience’s anticipation, is it time for applause or for more listening? In light of these frequent occurrences, musicians tend to take on a more relaxed body posture and less concentrated facial expressions to mark the end of a performance, often with a smile as if to say: “Yes, you can now applaud, boo, do what you want, it’s over”..

It is often a confounding moment when a performance of free improvised or experimental music starts or ends. A few seconds of silent hesitation denote the audience’s anticipation, is it time for applause or for more listening? In light of these frequent occurrences, musicians tend to take on a more relaxed body posture and less concentrated facial expressions to mark the end of a performance, often with a smile as if to say: “Yes, you can now applaud, boo, do what you want, it’s over”..

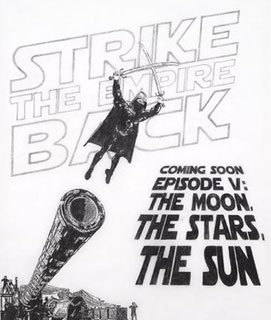

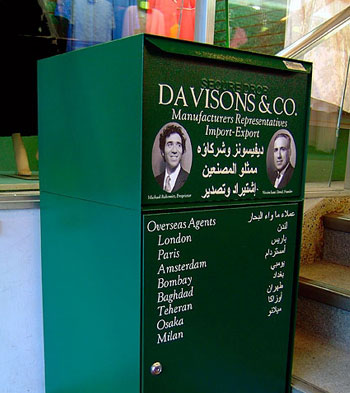

What do Jules Verne, Andree the Giant, Darth Vader and Sgt. Slaughter all have in common? Like a surreal game of Six Degrees of Separation, these characters are seamlessly linked in artist Michael Rakowitz’s latest exhibition at London’s Tate Modern entitled ‘The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own’ (2010). Employing the humour, wit and research strategies akin to investigative journalism, he deftly exposes the finely spun webs connecting seemingly disparate elements across times, geographies and histories. Rakowitz is interested in making the invisible, visible, and in revealing the latent circuits of power and politics that shape daily realities.

What do Jules Verne, Andree the Giant, Darth Vader and Sgt. Slaughter all have in common? Like a surreal game of Six Degrees of Separation, these characters are seamlessly linked in artist Michael Rakowitz’s latest exhibition at London’s Tate Modern entitled ‘The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own’ (2010). Employing the humour, wit and research strategies akin to investigative journalism, he deftly exposes the finely spun webs connecting seemingly disparate elements across times, geographies and histories. Rakowitz is interested in making the invisible, visible, and in revealing the latent circuits of power and politics that shape daily realities. U.S. under such restrictive measures, the date syrup’s circuitous route — having been produced in Iraq, trucked over to Syria, packaged in and shipped from Lebanon – seemed to echo that of refugee and migrant bodies fleeing the violence in Iraq.

U.S. under such restrictive measures, the date syrup’s circuitous route — having been produced in Iraq, trucked over to Syria, packaged in and shipped from Lebanon – seemed to echo that of refugee and migrant bodies fleeing the violence in Iraq.

How long have you been living in France?

How long have you been living in France?

which he was commissioned to compose.

which he was commissioned to compose.

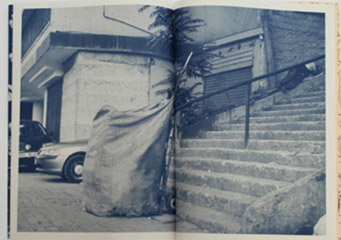

Unfinished (2007) and InBetween (2006) are the titles of the two series of works by photo-artist Hrair Sarkissian, born in Damascus in 1973, that we will discuss in this text. Both titles describe phases of transition, an ‘in-between’ in terms of both space and time. The photos of building shells in various Middle East cities (Unfinished) and the views of snowy landscapes, buildings and monuments in Armenia (InBetween) depict various transitory stages on the level of representation. In addition, the staging of the visible, the lavish, almost theatrical illumination of the rooms and the elegiac-style sepia effect refer to a real or imaginary past or future. Hrair Sarkissian’s works revolve around individual and ‘collective’ memory and identity.

Unfinished (2007) and InBetween (2006) are the titles of the two series of works by photo-artist Hrair Sarkissian, born in Damascus in 1973, that we will discuss in this text. Both titles describe phases of transition, an ‘in-between’ in terms of both space and time. The photos of building shells in various Middle East cities (Unfinished) and the views of snowy landscapes, buildings and monuments in Armenia (InBetween) depict various transitory stages on the level of representation. In addition, the staging of the visible, the lavish, almost theatrical illumination of the rooms and the elegiac-style sepia effect refer to a real or imaginary past or future. Hrair Sarkissian’s works revolve around individual and ‘collective’ memory and identity. to the time when Armenia was a Soviet Union republic and a popular holiday destination in the Soviet Union thanks to its warm climate. After the declaration of independence in 1991, holiday-makers stopped coming and new investors were not to be found. The partially incomplete building shells are already falling into disrepair but because it is too expensive to demolish them, they remain as ‘unwanted’ monuments to the fact that the country was not able to realise its objectives of economic upturn and prosperity. Laclau refers to the fact that every system is pervaded with constitutive ambivalences preventing complete totalisation as “dislocation”. Unlike ‘spatialisation’, dislocational effects are a temporal phenomenon. The temporalisation of space leads to a defixation of codified meanings. The fog and snow and the brownish coloration of Sarkissian’s photographs emphasise the aspect of temporality in a non-stabilised hypothetical construct of ‘collective identity’ intended to generate a certain we-consciousness but that is obviously full of cracks.

to the time when Armenia was a Soviet Union republic and a popular holiday destination in the Soviet Union thanks to its warm climate. After the declaration of independence in 1991, holiday-makers stopped coming and new investors were not to be found. The partially incomplete building shells are already falling into disrepair but because it is too expensive to demolish them, they remain as ‘unwanted’ monuments to the fact that the country was not able to realise its objectives of economic upturn and prosperity. Laclau refers to the fact that every system is pervaded with constitutive ambivalences preventing complete totalisation as “dislocation”. Unlike ‘spatialisation’, dislocational effects are a temporal phenomenon. The temporalisation of space leads to a defixation of codified meanings. The fog and snow and the brownish coloration of Sarkissian’s photographs emphasise the aspect of temporality in a non-stabilised hypothetical construct of ‘collective identity’ intended to generate a certain we-consciousness but that is obviously full of cracks.