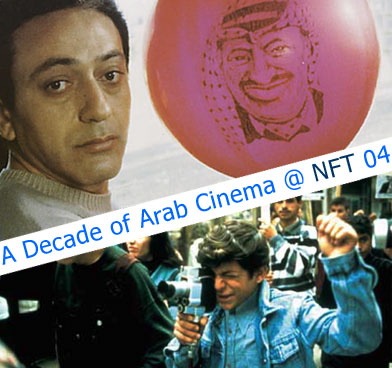

A Decade of Arab Cinema @ NFT, London

August 2004

The National Film Theatre Arab Cinema Season was the first of its kind in London and was held throughout August 2004. The season featured 17 films from 7 Arab countries, showing the diversity and quality of film making from the region in the last decade. This was attended by an audience of over 2,000 and reached an estimated 8 million people through extensive media coverage.

The National Film Theatre Arab Cinema Season was the first of its kind in London and was held throughout August 2004. The season featured 17 films from 7 Arab countries, showing the diversity and quality of film making from the region in the last decade. This was attended by an audience of over 2,000 and reached an estimated 8 million people through extensive media coverage.

A Citizen, an Inspector and a Thief (Mowaten we Mokhber we Haramy)

A highly entertaining tale interweaving the stories of an upper class struggling writer, a thief with a new found passion for self-styled literary criticism, a maid who is both their lovers and the cunning inspector.

A highly entertaining tale interweaving the stories of an upper class struggling writer, a thief with a new found passion for self-styled literary criticism, a maid who is both their lovers and the cunning inspector.

Bab el-Oued City

Taking place in Bab el-Oued, an impoverished neighbourhood in Algiers, the film follows Boualem, a young Algerian working in a French bakery. Simply desiring a quiet life, he finds himself living under a loudspeaker constantly blaring out angry sermons from the local mosque. Unable to stand the incessant admonitions, he tears down the loudspeaker and throws it into the sea, provoking the anger of a relentless mob. Set shortly after the country’s bloody riots of 1988, the film foretells the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Algeria, which would ultimately lead to a vicious civil war for much of the later half of the 90s. The film won the International Critics’ Prize at the 1996 Cannes Film Festival.

Taking place in Bab el-Oued, an impoverished neighbourhood in Algiers, the film follows Boualem, a young Algerian working in a French bakery. Simply desiring a quiet life, he finds himself living under a loudspeaker constantly blaring out angry sermons from the local mosque. Unable to stand the incessant admonitions, he tears down the loudspeaker and throws it into the sea, provoking the anger of a relentless mob. Set shortly after the country’s bloody riots of 1988, the film foretells the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Algeria, which would ultimately lead to a vicious civil war for much of the later half of the 90s. The film won the International Critics’ Prize at the 1996 Cannes Film Festival.

Canticle of the Stones (Nashidul Hajar)

Two Palestinian lovers, parted during the 60s when he is imprisoned for resisting the Israeli occupation and she sorrowfully emigrates to the US, come together again in Jerusalem some 18 years later. He works for an agricultural aid organisation, she is a scholar researching the meaning of sacrifice in Palestinian society. Around them rages the turmoil of the first Intifada. Michel Khleifi’s film boldly melds drama and documentary in exploring the personal and political.

Two Palestinian lovers, parted during the 60s when he is imprisoned for resisting the Israeli occupation and she sorrowfully emigrates to the US, come together again in Jerusalem some 18 years later. He works for an agricultural aid organisation, she is a scholar researching the meaning of sacrifice in Palestinian society. Around them rages the turmoil of the first Intifada. Michel Khleifi’s film boldly melds drama and documentary in exploring the personal and political.

Chronicle of a Disappearance (Segell ikhtifa)

‘To be or not to be ….a Palestinian.’ So writes the central figure in Elia Suleiman’s semi-autobiographical debut. Honoured as Best First Film at Venice in 1997, it is filled with often humorous vignettes, from a Palestinian woman’s comical use of an army walkie-talkie, to the contrast between a stream of excited Jerusalem-bound Japanese tourists and the silently chain-smoking Palestinians who observe them. Developing many of the themes and ideas he’d later employ to such great effect in Divine Intervention, Suleiman creates an affecting portrait of what it means to be a Palestinian, and the surreal dichotomy of being a people without a state.

‘To be or not to be ….a Palestinian.’ So writes the central figure in Elia Suleiman’s semi-autobiographical debut. Honoured as Best First Film at Venice in 1997, it is filled with often humorous vignettes, from a Palestinian woman’s comical use of an army walkie-talkie, to the contrast between a stream of excited Jerusalem-bound Japanese tourists and the silently chain-smoking Palestinians who observe them. Developing many of the themes and ideas he’d later employ to such great effect in Divine Intervention, Suleiman creates an affecting portrait of what it means to be a Palestinian, and the surreal dichotomy of being a people without a state.

Divine Intervention (Yadon ilaheyya)

A flying female ninja suicide bomber, a dialogue-free romance carried out between two lovers on opposite sides of an Israeli checkpoint, and a smiling balloon of Yasser Arafat floating peacefully above Jerusalem. These are only a few of the many treats on offer in Elia Suleiman’s majestic depiction of contemporary Palestinian life. Set during the final days of the Oslo Peace Process, such seemingly disparate vignettes are held together by Suleiman himself, his blank expression effortlessly evoking memories of Buster Keaton. He even manages a spot of slapstick destruction, as an Israeli watchtower comes crashing down. The film won the Fipresci Prize at Cannes.

A flying female ninja suicide bomber, a dialogue-free romance carried out between two lovers on opposite sides of an Israeli checkpoint, and a smiling balloon of Yasser Arafat floating peacefully above Jerusalem. These are only a few of the many treats on offer in Elia Suleiman’s majestic depiction of contemporary Palestinian life. Set during the final days of the Oslo Peace Process, such seemingly disparate vignettes are held together by Suleiman himself, his blank expression effortlessly evoking memories of Buster Keaton. He even manages a spot of slapstick destruction, as an Israeli watchtower comes crashing down. The film won the Fipresci Prize at Cannes.

The Extras (Al-Kompars)

Lovers meeting secretly at a friend’s place feel scared to the point of paranoia about being found out. Their frustrations seem temporarily resolved when the lover, who is an extra in a theatre, demonstrates what he does for a living. But ultimately their alienation returns as they seem to be extras in their real lives, not in control, secondary and marginal.

Lovers meeting secretly at a friend’s place feel scared to the point of paranoia about being found out. Their frustrations seem temporarily resolved when the lover, who is an extra in a theatre, demonstrates what he does for a living. But ultimately their alienation returns as they seem to be extras in their real lives, not in control, secondary and marginal.

Halfaouine – Child of the Terraces (Asfour Stah)

Young Noura is taken frequently to the public baths by his mother. Growing interested in women’s bodies, he is ejected from the feminine milieu in which he has felt comfortable, into the unaccustomed realities of a man’s world. Surprisingly frank in its depiction of sexuality (eavesdropping on a group of women as they make ribald jokes about cucumbers), the film offers a stylish, attractive take on the rigid sexual divide of Arab society, and was a considerable hit in Tunisia.

Young Noura is taken frequently to the public baths by his mother. Growing interested in women’s bodies, he is ejected from the feminine milieu in which he has felt comfortable, into the unaccustomed realities of a man’s world. Surprisingly frank in its depiction of sexuality (eavesdropping on a group of women as they make ribald jokes about cucumbers), the film offers a stylish, attractive take on the rigid sexual divide of Arab society, and was a considerable hit in Tunisia.

Nightfall

Director Mohamed Soueid catches up with a group of friends from the ‘Student Squad’ of the Palestinian Fatah movement. Portraying their drunken recall of the ‘good old days’ of the Lebanese Civil War, the film is at once touching, funny and poignant.

Director Mohamed Soueid catches up with a group of friends from the ‘Student Squad’ of the Palestinian Fatah movement. Portraying their drunken recall of the ‘good old days’ of the Lebanese Civil War, the film is at once touching, funny and poignant.

The Olive Harvest (Mousem al Zaytoun)

A tale of two brothers in the Palestinian Territories falling in love with the same woman, The Olive Harvest juxtaposes the personal drama with a depiction of the simmering tensions between Palestinian farmers and Israeli settlers. A festival hit around the world, the film has also accrued controversy for the director’s decision to use a mixed Palestinian and Israeli cast and crew, claiming the film was conceived ‘as a message of peace.’

A tale of two brothers in the Palestinian Territories falling in love with the same woman, The Olive Harvest juxtaposes the personal drama with a depiction of the simmering tensions between Palestinian farmers and Israeli settlers. A festival hit around the world, the film has also accrued controversy for the director’s decision to use a mixed Palestinian and Israeli cast and crew, claiming the film was conceived ‘as a message of peace.’

Rachida

Set during the darkest days of Algeria’s fight against Islamic fundamentalism, Rachida tells the tale of a vivacious young schoolteacher. When she refuses to plant a bomb in her school, she is shot point-blank by a gang of fundamentalists. Miraculously surviving, she retreats with her divorced mother to a small village. Once there, she resumes teaching and befriends one of her young students, unaware that the girl’s father is a terrorist. A powerful portrayal of a country torn apart by violence and archaic stigmas, with Rachida heart-breakingly summing up her plight, ‘I am in exile in my own country.’

Set during the darkest days of Algeria’s fight against Islamic fundamentalism, Rachida tells the tale of a vivacious young schoolteacher. When she refuses to plant a bomb in her school, she is shot point-blank by a gang of fundamentalists. Miraculously surviving, she retreats with her divorced mother to a small village. Once there, she resumes teaching and befriends one of her young students, unaware that the girl’s father is a terrorist. A powerful portrayal of a country torn apart by violence and archaic stigmas, with Rachida heart-breakingly summing up her plight, ‘I am in exile in my own country.’

Rana’s Wedding (aka Jerusalem, Another Day) (Al Qods fi yom Akhar)

Rana is given an ultimatum by her father to get married or return with him to Egypt and complete her studies. We follow her around on one hectic day in East Jerusalem as she attempts to make the final preparations for her wedding, valiantly trying to transcend the harsh realities of life under occupation, avoid the endless road-blocks and make it to the altar by four-o’clock. Abu-Assad creates a fitting testament to an ever-beleaguered and ever-proud people.

Rana is given an ultimatum by her father to get married or return with him to Egypt and complete her studies. We follow her around on one hectic day in East Jerusalem as she attempts to make the final preparations for her wedding, valiantly trying to transcend the harsh realities of life under occupation, avoid the endless road-blocks and make it to the altar by four-o’clock. Abu-Assad creates a fitting testament to an ever-beleaguered and ever-proud people.

Refuge (aka Deportation) (Al-Tarhil)

The ancient city of Hama in Syria in 1948-49 witnesses an influx of refugees following the Naqba (catastrophe) that saw the destitution of Palestinians after the formation of the state of Israel. The film develops its intertwining of personal lives with political events through two successive military coups in Syria and the repression that resulted.

The ancient city of Hama in Syria in 1948-49 witnesses an influx of refugees following the Naqba (catastrophe) that saw the destitution of Palestinians after the formation of the state of Israel. The film develops its intertwining of personal lives with political events through two successive military coups in Syria and the repression that resulted.

Sleepless Nights (Sahar al-Layali)

A box-office sensation when it opened in Egypt, and a hit with critics too. Following the lives of four upper-middle-class couples who are working through their relationship problems, the film was applauded for its frank depiction of marriage, adultery and sexuality. An unmissable trend-setter in new Egyptian cinema.

A box-office sensation when it opened in Egypt, and a hit with critics too. Following the lives of four upper-middle-class couples who are working through their relationship problems, the film was applauded for its frank depiction of marriage, adultery and sexuality. An unmissable trend-setter in new Egyptian cinema.

So Near Yet So Far (Karib Baid)

So Near Yet So Far takes as its starting point the killing of the child Mohamad Durra in the arms of his powerless father. The event became a cause célèbre around the world and, in particular, a source of reflection and revolt for many children in the Arab world. Raheb undertakes an emotional journey tracing the formative effect of the Palestinian cause on Arabs from different countries, whether they embrace or reject it.

So Near Yet So Far takes as its starting point the killing of the child Mohamad Durra in the arms of his powerless father. The event became a cause célèbre around the world and, in particular, a source of reflection and revolt for many children in the Arab world. Raheb undertakes an emotional journey tracing the formative effect of the Palestinian cause on Arabs from different countries, whether they embrace or reject it.

Terra Incognita (Al-Ard Al-Majhula)

Ghassan Salhab belongs to the post-Civil War generation of young directors who were adolescents when Lebanon erupted in 1975. His second feature focuses on the young people of Beirut. After so many years of destruction, emigration and the inevitable emotional turmoil which comes in its wake, he portrays a generation suspended in time. They are caught hanging in the present, daring not to look back, even less willing to look into the uncertain future. The film is especially daring in terms of its sexual frankness and nudity.

Ghassan Salhab belongs to the post-Civil War generation of young directors who were adolescents when Lebanon erupted in 1975. His second feature focuses on the young people of Beirut. After so many years of destruction, emigration and the inevitable emotional turmoil which comes in its wake, he portrays a generation suspended in time. They are caught hanging in the present, daring not to look back, even less willing to look into the uncertain future. The film is especially daring in terms of its sexual frankness and nudity.

West Beirut (West Beyrouth)

Lebanon 1975. Civil war has erupted and Beirut finds itself split into two halves – West and East. In the predominantly Muslim West, childhood friends Tareq and Omar, along with a young Christian girl, take advantage of the cancellation of school and roam the city in search of adventure, excitement and, inadvertently, the local brothel. Formerly Quentin Tarantino’s assistant cameraman, Doueiri fashions a film imbued with the thrills of adolescence, while never forgetting to show the painful absurdity of war.

Lebanon 1975. Civil war has erupted and Beirut finds itself split into two halves – West and East. In the predominantly Muslim West, childhood friends Tareq and Omar, along with a young Christian girl, take advantage of the cancellation of school and roam the city in search of adventure, excitement and, inadvertently, the local brothel. Formerly Quentin Tarantino’s assistant cameraman, Doueiri fashions a film imbued with the thrills of adolescence, while never forgetting to show the painful absurdity of war.

Women’s Wiles (Keid ensa / Ruses de femmes)

Evoking the spirit of Scheherezade from ‘1001 Nights’, Benlyazid’s film focuses on a beautiful merchant’s daughter, Lalla Aicha, with whom the king’s son falls in love. Their verbal sparring centres around one question: whether men are cleverer than women. Aicha refuses to concede her point, even when locked up in a cellar until she changes her mind. Instead she devotes her time to playing tricks on the prince. An enjoyable slice of arabesque with a feminist twist.

Evoking the spirit of Scheherezade from ‘1001 Nights’, Benlyazid’s film focuses on a beautiful merchant’s daughter, Lalla Aicha, with whom the king’s son falls in love. Their verbal sparring centres around one question: whether men are cleverer than women. Aicha refuses to concede her point, even when locked up in a cellar until she changes her mind. Instead she devotes her time to playing tricks on the prince. An enjoyable slice of arabesque with a feminist twist.