Ongoing: The Unfinished Tales of Michael Rakowitz

Nora Razian

What do Jules Verne, Andree the Giant, Darth Vader and Sgt. Slaughter all have in common? Like a surreal game of Six Degrees of Separation, these characters are seamlessly linked in artist Michael Rakowitz’s latest exhibition at London’s Tate Modern entitled ‘The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own’ (2010). Employing the humour, wit and research strategies akin to investigative journalism, he deftly exposes the finely spun webs connecting seemingly disparate elements across times, geographies and histories. Rakowitz is interested in making the invisible, visible, and in revealing the latent circuits of power and politics that shape daily realities.

What do Jules Verne, Andree the Giant, Darth Vader and Sgt. Slaughter all have in common? Like a surreal game of Six Degrees of Separation, these characters are seamlessly linked in artist Michael Rakowitz’s latest exhibition at London’s Tate Modern entitled ‘The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own’ (2010). Employing the humour, wit and research strategies akin to investigative journalism, he deftly exposes the finely spun webs connecting seemingly disparate elements across times, geographies and histories. Rakowitz is interested in making the invisible, visible, and in revealing the latent circuits of power and politics that shape daily realities.Things are never what they seem; an old adage that takes on a new urgency in Rakowitz’s politically resonant productions. It is a maxim that sits at the core of his investigations and stems from personal curiosities awakened through familial links and everyday encounters. Over the last few years, Rakowitz has focused his attention on the ongoing war in Iraq and on what he calls the ‘cultural invisibility’ of Iraq in the U.S. It may be relevant to mention that Rakowitz himself is of Iraqi-Jewish heritage, and while for many others cultural affiliations are often considered taboo, Rakowitz is quick to point that his family history and lineage are primary motivators for his art practice.

The 2003 U.S-led invasion of Iraq, as well as the climate post-September 11th, spurred the already socially-engaged Rakowitz to focus his efforts on trying to reconfigure public understanding of, and relationship to, his country of heritage. Since then he has produced a number of projects which openly state that his focus on Iraq will continue as long as the matter remains obscured to the general public in the U.S.

He said in 2006 in Nick Stillman’s ‘Conversations with Michael Rakowitz’ “I really do believe in certain aspects of cultural exchange coming from this horrible situation, and also in finding ways in which one’s culture can be disseminated through things like crafts and food and bringing that into the artistic discussion rather than just using night vision video or the things you see on CNN.”

As such, an element of dialogue underpins much of Rakowitz’s work. He is, however, keenly aware of the complexities involved in engaging an audience in a productive dialogue, as well as the limited scope of his work in engendering any real social or political change. He posits himself as a problem maker rather than purporting to offer any solutions, pushing these problems to the fore in the hope of igniting some form of conversation.

In The invisible enemy should not exist (2007), Rakowitz reconstructs looted objects from Iraq’s National Museum out of recycled Middle Eastern food packaging. He painstakingly reconstructs each object using references sourced from Interpol reports, archeological archives and university research centers. The objects’ troubled trajectories are brought to light through illustrated wall panels depicting, in comic-book like fashion, the story of the Ishtar Gate and of Dr. Donny George, the former director of the museum, whose character is central to the narrative structure of the exhibition. George’s story of quiet resistance against the Ba’ath party, his role as a drummer in a Deep Purple cover band, and his forced flight from Iraq after the U.S invasion, provide the narrative arches through which the wider complexities of the war’s effects are elucidated.

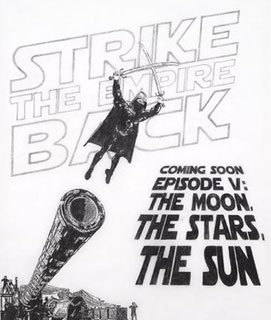

In The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own (2009), Rakowitz explores the links between fantasy and reality by probing Saddam Hussein’s’ fascination with Star Wars, linking this to Jules Verne, the French Revolution and the World Wrestling Federation. Similarly to The invisible enemy should not exist, he uses handwritten and illustrated wall panels to weave a narrative, connecting it to the more sculptural pieces on display such as reconstructed helmets that trace the design trajectory for those of Saddam’s Fedayeen forces, from Samurai head gear up to Darth Vader’s mask, or a replica of the Swords of Qādisīyah monument. In both works, the narrative follows arches of association, symbolism and meaning with no clear or distinct resolution – a structure that points to Rakowitz’s affinity for the fragmented structures of the post-modern novel, such as the writings of Dave Eggers.

These works illustrate his ambition to reveal obscure networks and relationships, connecting the pieces in each installation to other references and geographies. The hallmark of failure runs through each of his works – whether it was the failure to import one ton of dates into the US in Return (2006-ongoing), the failure of US forces in Iraq, or the failure of Saddam to hold on to his reign. The ‘spectacle of failure’ is something Rakowitz acknowledges to be an important, recurrent theme in his work. He does not allege to offer solutions, but to “problematize problems”, in order to create the context and content which engender enriching conversations. “There is a specific use in the spectacle of failure; it can create a conversation. When you drop a lot of books in front of a building, people will stop and help you to pick them up. That’s the kind of thing that can be a start for a conversation” (Nick Stillman’s ‘Conversations with Michael Rakowitz’).

Although Rakowitz has completed a number of distinct but interrelated projects over the years, a unique style of storytelling seems to lie at the core of his practice. His provocatively constructed narratives and symbolic storylines bind his projects together, in many cases acting as distinct chapters in what might be imagined as an overarching novel in progress. Storytelling, for Rakowitz, serves as a way of “coming to terms with the world and giving it form- through personal narratives and unique encounters that intersect and unfold to create a multilayered experience of reality.” Through his work we learn how fiction and fantasy have influenced political and military ambitions, and how the circuitous route of trade exports from Iraq mirrors those of humans seeking refuge. As such, he joins the ranks of artists such as Hito Steyerl, Walid Raad and Omer Fast, who employ storytelling in myriad ways to provide counter-narratives that interrupt and explode dominant media discourse and officially sanctioned histories which conventionally mediate perceptions of local and global events. As art historian T.J. Demos has commented in ‘Storytelling in/as contemporary art’ (2010), the drive to narrate in this way has “led to alternative forms of knowledge production, to new histories that include those who have suffered or otherwise been rendered invisible, as well as to innovative ways of relaying experience by rethinking representation.” Yet, while one is keenly aware of his voice within the narrative, Rakowitz resists presenting facile points of closure or conclusion.

Rakowitz’s personal voice is central to each of his projects, whether it is through his performative presence as artist and store clerk in Return (2006 – ongoing), the illustrated and handwritten wall panels in The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own, or through narrated, written or presented accounts of his projects. He seems keenly aware of how interactive projects such as Return are disseminated following their actual completion, and how quickly their meaning can be deadened when placed within the sometimes static context of galleries and museums. As such, Rakowitz diligently controls how each project is presented to the public by wrapping it in a tight storyline that still allows for minor alterations depending on the audience. While he acts as a mediator for the work, he remains astutely aware of the “conventional division between artist as storyteller and the viewer as audience.” He provides alternative entry points and circumvents any facile answers, quite in line with philosopher Jacques Rancière’s notion that “emancipation comes only when we all become storytellers – that is when the audience joins the artists in the act of producing meaning.”(Quotes are from ‘Storytelling in/as contemporary art’ 2010).

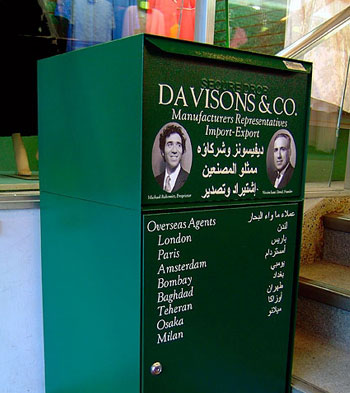

Rakowitz’s position as storyteller is most clearly articulated in the ongoing project Return. Initially conceptualized in 2004 as Return (Drop Box), and commissioned by the Jamaica Center for the Arts and Learning in New York, the project took the form of a parcel service, where the public could drop off small items to be posted to Iraq. The initial project was set up in a Korean-owned clothing store and import/export business, and though some small items were in fact sent to Iraq, the project’s main objective remained symbolic.

In 2006, Rakowitz added a new dimension to it. During one of his habitual visits to Shahadi Imports, a grocery store in New York City specializing in Middle Eastern products, he came across a can of date syrup. Although it was labeled as a product of Lebanon, the shop owner informed him that it was in fact a product of Iraq. Although Iraqi goods were allowed into the U.S. at the time, prohibitive customs laws and exorbitant tariffs rendered engaging in any form of trade economically unviable. To reach the

U.S. under such restrictive measures, the date syrup’s circuitous route — having been produced in Iraq, trucked over to Syria, packaged in and shipped from Lebanon – seemed to echo that of refugee and migrant bodies fleeing the violence in Iraq.

U.S. under such restrictive measures, the date syrup’s circuitous route — having been produced in Iraq, trucked over to Syria, packaged in and shipped from Lebanon – seemed to echo that of refugee and migrant bodies fleeing the violence in Iraq.Spurred by this discovery and the marked absence of any goods bearing the label ‘product of Iraq’ in U.S shops, Rakowitz reopened his grandfather’s business, Davisons & Co., with the aim of importing the first Iraqi dates into the U.S. in over 30 years. The proposal for Return – produced as part of Who Cares (2006), a Creative Time initiative aimed at critically exploring relationships between cultural production and social action – sought to explore what kind of return, both fiscal and existential, could be acquired through this transaction. As Rakowitz says, “I wanted Return to isolate and examine all of the really horrible inequities that are involved in this war.”

The words ‘We sell Iraqi dates’ prominently displayed along with the Davisons and Co. logo (a stencil style portrait of Rakowitz alongside one of his grandfathers) in both Arabic and English, provided a visual jolt to passers-by unaccustomed to seeing signage related to Iraq in commercial settings. The storefront logo also provided contextual information with Rakowitz prominently displaying himself in relation to both his grandfather and Iraq, and thus highlighting notions of continuity, tradition, and lineage.

Upon entering, visitors were greeted with a set-up that looked something like a shop display: items posted on the walls included a timeline illustrating the history of dates, various versions of the Iraqi flag after each coup or revolution, a chronology of the the history of the Iraqi people, as well as an invoice for one ton of Iraqi dates. Not keen to provide merely a banal context, Rakowitz’s presence in the store and the narratives weaved around that, were key components in making the project work in the way it did. While on site in the ‘store’, Rakowitz’s simultaneous persona as artist and clerk worked to raise questions about his family history, the process of importing dates and the current state of crisis in Iraq.

In parallel to the actual store itself, Rakowitz kept a blog detailing events and interactions in the shop as well as documenting communication with his trade partners in Iraq. Functioning as an important component of the project’s overall narrative, the blog elucidates the transactions that took place across different aspects of the project, while providing insight into the artist’s doubts and triumphs throughout the process.

Rakowtiz’s motivations to provide access to counter-narratives and eclipsed histories tinge his undertakings with a distinct pedagogical air. He sees his projects as self-education, occurring within a shifting framework constructed through continually evolving relationships with audiences and stakeholders. His practice follows art historian Grant H. Kester’s notion of dialogical aesthetics, or what others have termed “new genre public art”, “conversational art” or “littoral art” (Theory in Contemporary Art Since 1985 (2005)). Kester categorized artists working in this way as challenging assumptions about the relation between art, society and the political world. Central to this is the continued implication of both the artist and audience in the production of meaning, where the outcome and form of the project remains undetermined until its allotted time ends. Rakowitz has firmly roots himself within this categorization, believing “full-heartedly in a public art that enlists its public as vital collaborators in the production of meaning” (‘Spectacles of Failure’, Provisions Library Blog).

As such, Return is a continually evolving work. In its current state, it has been relegated to the sanctified space of the gallery, and while this provides a form of access to the project, it also points to the largely numbing effect of display spaces on interactive projects. While the artist recognizes this, it is ignored for the aim of keeping the project alive, even if in an incubated state. As such, Rakowitz’s practice straddles both the display space and the public realm. While locating himself both within and outside the art world, he is mindful of the gallery space and of its potential impact on his practice.

In its current form, Return now functions more like a documentation of the interactive project; the multimedia display includes Iraqi products, a picture of the dates and their packaging, and most importantly, a documentary video of the project narrated by Rakowitz himself. Future plans for the reactivation of the project include the opening of an Iraqi restaurant in Chicago, fusing the format of Return with that of Enemy Kitchen, the latter being an ongoing project from 2004 where the artist collaborates with his mother to compile traditional Iraqi dishes and teach them to various publics.

The continual reincarnation of Return illustrates Rakowitz’s commitment to perpetuating an open conversation around the ongoing war in Iraq: “I prefer to keep these things ongoing; I refuse to say that it’s over because that would be admitting that the problem is solved. I would love for these projects to go away, because that would mean that the problem would not be around anymore.”

Nora Razian

Michael Rakowitz was featured in the New Ends, Old Beginnings exhibition.